Host competence: A malaria tale!

- Tabeth

- Oct 23, 2022

- 2 min read

Hi all, it’s been a while since we touched base with this malaria journal. Welcome back!

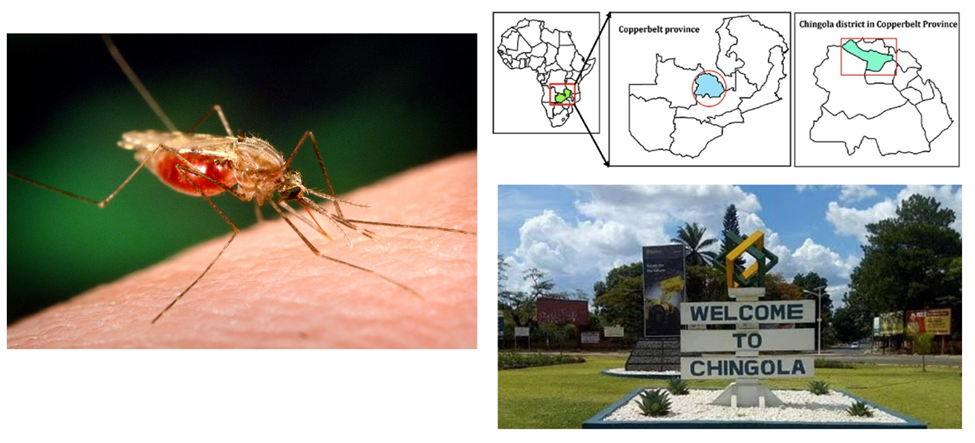

This week I will discuss what makes you and I more vulnerable to malaria infection than others. Malaria transmission involves two hosts of the parasites: mosquitoes and people. There are certain factors that contribute to the transmission of malaria: one is the abundance of mosquitoes and two is how parasites are distributed within a community, among others. It is hypothesized that 20% of all macroparasites (mosquitoes) within a community are distributed among 80% of hosts but I am sure this number would be reduced if we fact in vector control interventions. As the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends, 80% of the population should be sleeping under mosquito nets to achieve universal community protection. If this is followed religiously by vector control programs, then 20% of the mosquitoes only affect the population left unprotected. Although the SIR model assumes that the likelihood of being infected is the same for each person, that is not the case in an actual population due to several reasons. Therefore, that 20% can be reduced further because the likelihood of being infected by mosquitoes is not the same for all individuals. Some people are highly attracted to mosquitoes than others. For instance, blood group O, and pregnant women (because of increased hormones) attract more mosquitoes compared to others.

To explain the concepts above, we can look at both the competence of humans and mosquitoes as hosts. People that are not protected will have a higher parasite aggregation in that community which then makes the Plasmodium parasites overdispersed as shown in the graph. Since these people will harbor more parasites than others, they are also likely to shed more parasites to mosquitoes and therefore to other unprotected humans. They are also likely to be infected again with the same parasites they shed. Although this may reduce the fitness of people, in the long run, they do develop immunity to malaria. As a result, visitors (who have never been exposed to malaria) of malaria-endemic areas are at a higher risk of being infected compared to the local people. Additionally, children under the age of five are equally at a higher risk of infection because of reduced immunity but with easy access to good anti-malarial drugs, all these infections can be fought off.

Finally, insecticide resistance and climate change (increased rainfall and temperature) can affect the competence of mosquitoes to transmit diseases. Transmission of malaria is highest in countries or seasons with high rainfall and temperature. However, in a study that was conducted in South Africa, there was an increase in malaria cases from an average of 600 to over 2 000 per month in winter, usually a period of low malaria transmission. This was observed when they switched insecticides from DDT to deltamethrin resulting in extreme resistance of Anopheles funestus: a mosquito that is highly anthropophilic. In short, the higher the number of resistant mosquitoes, the less they can be controlled by interventions, the more bites they can inflict on humans and infect them, the more they will be infected in return and reinfect.

Sources

Maharaj, R., Mthembu, D.J. and Sharp, B.L., 2005. Impact of DDT re-introduction on malaria transmission in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Medical Journal, 95(11), pp.871-874.

Wood, C.S., 1974. Preferential feeding of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes on human subjects of blood group O: A relationship between the ABO polymorphism and malaria vectors. Human biology, pp.385-404.

Comments