“…With tears and toiling breath…”

- Tabeth

- Sep 1, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2022

Hello everyone,

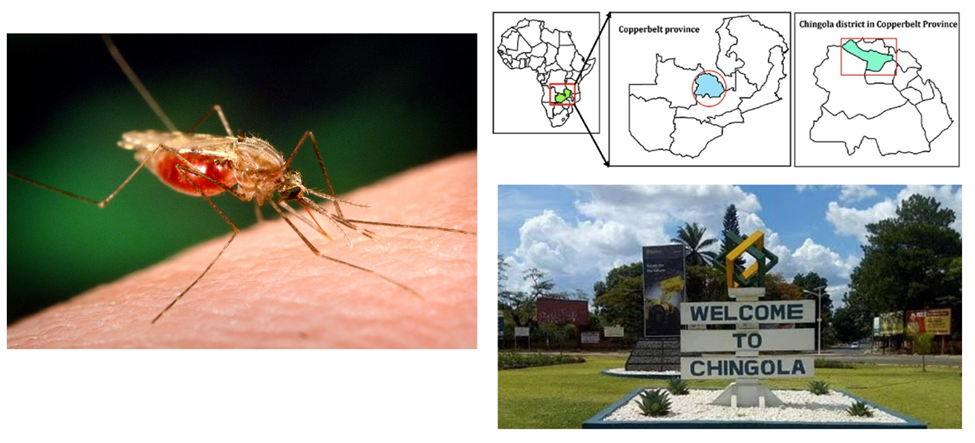

The title of this blog is the words of the fragment of a poem by Ronald Ross, written in August 1897 after he discovered malaria parasites in anopheline mosquitoes fed on malaria-infected patients. As I mentioned earlier in my previous post, this channel is about malaria, its vectors, and the parasites that cause it. This week we will only focus on the disease and the parasites.

Malaria is a word that is believed to have originated from the Italian “mal’aria” which means “spoiled air” although is not substantiated. Between 1878-1879, malaria was understudied as this is the same time studies of microorganisms that cause infectious diseases were being developed by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. However, in 1880, Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran discovered malaria and mosquitoes as vectors. From there onwards in 1897, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch discovered avian malaria. The human malaria was discovered by the Italian scientists Giovanni Battista Grassi, Amico Bignami, Giuseppe Bastianelli, Angelo Celli, Camillo Golgi and Ettore Marchiafava between 1898 and 1900. Giovanni Batista Grassi and Raimondo Filetti were the first to coin the names Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malariae in 1890. Grassi was also the first to describe the life cycle of the parasites in 1899. In 1897, Plasmodium falciparum was introduced by American William H Welch, and in 1922, the fourth malarial parasite Plasmodium ovale was found by John W. W. Stephens.

This disease is caused by the aforementioned parasites which are transmitted by an infective female Anopheles mosquito. The latest 2021 report shows that in 2020, there were 241 million cases which were higher as compared to 2019 with 227 million cases. The death toll in 2020 stood at an estimated 627 000, which was an increase of 69 000 deaths from the previous year. This increase was mostly attributed to service disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although, I do not know if this also accounted for the fact that malaria elimination has been facing challenges of drug resistance in the parasites and insecticide resistance in the vectors. The covid-19 pandemic just made it worse. So, I do not think we should be giving most of the credit to the pandemic. We have been in this situation far too long, especially in most African countries. Although there are approximately 2000 malaria cases in the United States per year, most of the global cases and deaths are prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This is because both the parasites and vectors need high temperatures for their survival and the tropics offer that environment.

The severity of malaria depends on the species of Plasmodium. As far as we know, many have been described but only five (Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi) cause this disease in humans. Additionally, P. knowlesi also infects macaques in Southeast Asia. This makes it difficult to control malaria as there is always a reservoir of parasites and therefore, continued disease transmission. Of the five parasites, P. falciparum causes severe infections and if not treated properly, death may follow. Although malaria is fatal, prevention of illness and death is usually possible. This can be done either by controlling the abundance and distribution of the mosquitoes or treating the infections. This is because, for continued malaria transmission, both the parasite and vector are needed. If this symbiotic relationship (Figure 1 stages 1 and 8) can be disrupted, malaria transmission would be terminated.

Figure 1: Malaria transmission cycle in the mosquito and human. (CDC photo)

Malaria presents itself with a fever, chills, sweating, headache, tiredness, nausea, vomiting, and muscle aches which usually come after weeks of getting bitten. Anemia and jaundice may also be the result of malaria due to the loss of red blood cells. It can be diagnosed in three different ways, but the standard rule is the microscopic examination of blood cells (Figure 2). However, a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) can also be used to quickly detect malaria antigens.

Figure 2: Blood smear from a patient with malaria; microscopic examination shows Plasmodium falciparum parasites (arrows) infecting some of the patient’s red blood cells. (CDC photo)

In order to eradicate malaria, WHO has set guidelines that countries must follow. However, before eradication can happen, we must first eliminate it. In malaria terms, “elimination” is local or regional while eradication is “global elimination. ” Eradication is not achieved until malaria is gone from the natural world. These guidelines are divided into two:

1) Case management - Malaria is diagnosed and treated quickly with a recommended antimalarial drug to keep the illness from progressing and to help prevent further spread of infection in the community. Usually what is given is Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), which is a combination of two or more drugs such as artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem) and artesunate-mefloquine.

2) Prevention - Involves the use of insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying. The former is meant to protect humans from mosquito bites while the latter reduces the abundance of indoor resting mosquitoes. Other interventions are larval control and mass drug administration, just to mention a few.

It is important that these guidelines are followed. If we do not abide by them, we will be chanting Ronald Ross’ words, except I am sure when he wrote them, it was a eureka moment. However, for us, it will be:

“…With tears and toiling breath…”

Mosquitoes and parasites will finish us all!

Sources:

Cox, F.E., 2010. History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites & vectors, 3(1), pp.1-9.

Liu, W., Li, Y., Learn, G.H., Rudicell, R.S., Robertson, J.D., Keele, B.F., Ndjango, J.B.N., Sanz, C.M., Morgan, D.B., Locatelli, S. and Gonder, M.K., 2010. Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature, 467(7314), pp.420-425.

As someone with zero background in diseases, pathogens, etc. I found your life cycle charts very helpful and easy to understand. I think something that makes your writing on malaria so interesting is your personal ties to the disease from growing up in Zambia. The idea of eradication sounded improbable to me initially, but I found in my own reading that the world’s first effective malaria vaccine was approve in 2021. This gives me some hope that eradication might be closer than I realized. I also read that malaria mortality and incidence rates have not changed appreciably since 2015 which is unnerving.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)00729-2/fulltext